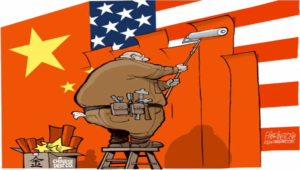

Reflection of China’s Belt and Road Initiative

Source: Skinner 2022

Undoubtedly, the Chinese BRI project was launched as part of China’s increasingly assertive approach, which we have seen especially in the last few years. It is another step towards achieving economic and political dominance in China’s immediate regions and, subsequently, in the whole world. Let us recall that the historical Silk Road was built primarily for trade and exchange and for the spread of Buddhism. This time, however, it is more associated with the spread of the influence of state-controlled capitalism and the Chinese Communist Party. In the context of the BRI’s power background, it is necessary to understand the way the Chinese leadership thinks about the world.

China’s way of thinking and perceiving the world around it, as well as its way of achieving its goals, is a great mystery to many Western observers. From a geoeconomic perspective, China’s behaviour tends to promote multilateralism. The Chinese themselves are also vocal about this because they know that this is the only way to expand into Western markets and gain the trust of Western politicians. However, if we take a closer look at China, we can see that the Chinese concept of multilateralism does not correspond with reality. It is based on national sovereignty, national interest, national power and national wealth. (Zhang – Alon – Lattemann 2018: 25).

A few years ago, a publication by a Chinese officer entitled The Chinese Dream was introduced, in which a strategy called the Hundred-Year Marathon was mentioned extensively (Pillsbury 2014: 302). It is a complex and secret strategy to replace America as the leading global power. Although the book is not the only one that has received enormous interest at the highest political levels. For many years, a set of publications have been popular among Chinese elites that focus on a specific period of Chinese history dating back to approximately 475 B.C., collectively referred to as the Warring States period (Pillsbury 2014: 48). Master Sun’s writings, which are known worldwide as: On the Art of War, have been subjected to detailed scrutiny and study in China. The writings fit into the Warring States period and tell the story of the power rivalry of the seven most powerful empires, from which a single hegemon eventually emerges to unite China (Vojta 2014: 10). In this highly competitive and hostile environment, the empire had to develop the skills of strategic foresight and anticipation of several possible alternatives to the situation (Vojta 2014: 10).

Another popular publication from the Warring States period is a novel called Tales of the Three Empires, which tells the story of the famous Battle of Red Cliff. The novel refers to the two famous Chinese emperors who clashed in a struggle for complete domination of China, using subterfuge and stratagem during the struggle. Then there is the writing entitled Thirty-Six Stratagems, which was instrumental in shaping Chinese strategic thinking (Xiaochun 1990: 5). They all belong to the series of treacherous plots of ancient military strategists. They also correspond to the Taoist style of yin and yang transformations. It is a work summarizing a set of „dirty“ tricks used by ancient emperors that have become required and indispensable reading for every army conscript or officer in China today. However, the work is also widely studied and interpreted across the civilian sphere (Xiaochun 1990: 5).

A few years ago, a publication by a Chinese officer entitled The Chinese There are pieces of evidence that The Warring States ethos has become mainstream thought in China. The strategy of The Hundred-Year Marathon, which draws on the basic ideas and wisdom of the Warring States period, has been put into practice by officers of the Chinese military, who have, to a Western observer, incredible powers in China, including, for example, the civilian leadership, demographic policy, the tax system and economic measures (Pillsbury 2014: 54). However, this plan has always been carefully hidden from the world, as has the fact that contemporary Chinese strategists draw heavily on a historical era of antagonisms, duplicity, subterfuge, and brutality in making their plans. Instead, everyone else is presented with the desire for a Confucian world full of kindness and sincerity, which China wants to use to fool its opponents and hide its true face.

Let’s take a look at the elementary points of Chinese strategy by Michael Pillsbury presented in his publication called The Hundred-Year Marathon (Pillsbury 2014: 41). Looking at those, we can simply find some connections with BRI.

Induce complacency to avoid alerting your opponent

One of the basic lessons of the Warring States period is to pretend that there is no comprehensive strategy for gaining power. To act as a friend of the hegemon while secretly working for its internal disintegration. Wait for its tight bonds to fray and its cohesion to loosen, exactly in the spirit of the old adage: „replace the beams and pillars with rotten timber“ (Xiaochun 1990: 10). Within the first element of the strategy, BRI works primarily in close cooperation with the Confucius Institutes spread around the world. The aim is to disseminate the desired Chinese narrative. For this purpose, educational institutions and think tanks have been selected as the best. In this way, China gains its die-hard supporters and unwavering backers in faraway countries among experts and academics who propagate the narrative, legitimizing it while relativizing the counter-arguments of anyone who disagrees with the narrative. We know of such cases in the Czech Republic, where scandals have emerged at Charles University related to the redistribution of money provided by the Chinese embassy among academics (Prague Post 2019). Confucius Institutes are indispensable in the context of BRI as they help to move the local societies and political representations in the „right“ direction. At the same time, they seek to maximize local perceptions of China and individual politicians to ensure a warm and friendly reception of the BRI and China’s related demands, thereby sowing division in the political structures.

Manipulate your opponent’s advisers

Recruiting opponents‘ advisors have been considered an elegant and effective way of achieving victory in the measurement of power since ancient times in China (Vojta 2014: 162). BRI is a very flexible strategy that allows one to „recruit“ collaborators in the ranks of the opponent. Then, they have the primary task of shaping the opinion of the general public and politicians in the locality, spreading the narrative promoted by China, or gaining additional collaborators and information from the highest political circles. Their task is to denigrate and vilify those who can see through Chinese intentions; therefore, they are not friendly to China. This practice is particularly evident in the Czech environment, for example, in the long-standing efforts to discredit the Sinopsis server through domestic business entities and educational institutions (Beach 2017).

If we look at the whole issue through the lens of the Warring States era power struggle, we find that China has no interest in mutually beneficial cooperation. China’s influence on the individual EU Member States was designed to reinforce the divisions between them and to gain a ‚mentor‘ within the structures of the opposition, someone who will help spread the necessary narrative that portrays China as a peaceful trading partner to trade without fear.

China has been quite successful in gaining the opponent’s advisors. Perhaps the most interesting case is that of the former EU ambassador to Beijing, who left the civil service to become a paid advisor to Huawei, which bids for state contracts for strategic communications around the world. Moreover, the company is being suspected of passing sensitive data to Chinese intelligence services (Godement – Vasselier 2017: 77). Another example is the former head of the French finance minister who became a head of a private French-Chinese investment fund. One can also name a former mayor of Antwerp who admires China. Another is a former member of the Supreme Council of the Bulgarian Socialist Party, which runs the BRI association in Bulgaria (Godement – Vasselier 2017: 77).

Be patient—for decades or longer—to achieve victory.

The Hundred-Years Marathon is a complex strategy that has been implemented very slowly and has been artfully kept secret until now. The BRI operates in a very similar way, except that instead of trying to keep it secret from the start, there has been an effort to present it as kindly as possible, using the kind words of win-win cooperation or peaceful economic development for all. But the truth is that the BRI is gradually growing in strength, slowly promoting Chinese national interests in more and more countries. The key to success is not to irritate the hegemon by moving too fast and too obviously. The Chinese therefore see success in a subtle and slow strategy (Pillsbury 2014: 58).

The Chinese have learned from the Warring States period that great victory never comes quickly, and success requires a good deal of patience. The BRI is seen as a massive long-term strategy which will evolve over decades (Zhang – Alon – Lattemann 2018: 25). They were inspired by the old Chinese axiom: ‚secretly pull the firewood from under the cauldron‘ (Xiaochun 1990: 91).

Steal your opponent’s ideas and technology for strategic purposes.

On this point, the benefit of the BRI is clear. Within the New Silk Road, huge sums of money are being made available to invest in infrastructure connecting the participating countries. However, this funding is often given to national champions, prominent businesses and companies directly supported by the government. They act as the driving force in an aggressive fight against foreign competition, which Chinese companies are trying to bring under control. The result is various forms of partnership between Western and Chinese companies, which often end in bankruptcy and scandals as same as the theft of intellectual property (Blumenthal – Zhang 2021).

After that, the know-how stolen in China is transferred to domestic companies. Stealing technologies and know-how from western companies has become a regular procedure within the Chinese economic expansion (Pillsbury 2014: 58). We can name, for example, the huge number of cyber attacks carried out by the Chinese hacker army directly linked to Beijing, which numbers around 50,000 or 100,000 hackers (Del Monte 2019: 102). In this way, China is able to quickly improve its position in the field of modern military technologies. Also, China manages to steal strategic information and then use it to advance itself (Dahir 2018).

Basically speaking, BRI is to become a kind of platform that will first create an infrastructural communication network, perhaps prospectively also something like an alternative Internet, which will be used by China to „borrow“ information of any kind, as it is a very complex initiative affecting many social, economic, political and cultural sectors within countries around the world. It is not hard to imagine that in the future, the BRI will link scientific and technological institutes or enterprises around the world.

Military might is not the critical factor for winning a long-term competition

There is no doubt about the benefits of BRI in a struggle without the use of military force. The New Silk Road was created as a tool to spread Beijing’s power in a „good way“. At the same time, it is an economic tool for advancing Chinese national interests through multilateral trade platforms, with China’s economy serving as its greatest weapon (Dogan 2021: 111). However, it should be kept in mind that when the time comes, the BRI will also be able to create the conditions and provide indispensable arguments for the expansion of Chinese military power. This is based on China’s efforts to build military bases or strategic ports along the BRI, such as Djibouti and El Salvador (Garlick 2020: 191). Hence the two-faced nature of Chinese behaviour. The speeches and declarations of the Chinese president and other leaders about the multilateral nature of the BRI are just part of China’s actions in the spirit of the saying „crossing the sea by treachery“ (Xiaochun 1990: 1).

Recognize that the hegemon will take extreme, even reckless, action to retain its dominant position

Despite the two faces and all the evasions, China is counting on a situation where Sino-US relations will reach a breaking point. Then a clash will be inevitable. Accordingly, it is using the BRI to acquire key technologies for disruptive weapons development, which will be used to hit the United States weaknesses, i.e. to take advantage of the perceived asymmetry (Liang – Xiangsui 1999). The BRI is also able to contribute to the realisation of this point by significantly helping to undermine US power. Furthermore, it is clear that the commercial sphere is becoming indispensable to the advanced military development technologies, the development of which is being enhanced by the BRI. That makes China one of the most advanced countries in the field of artificial intelligence research today (Komarraju 2021). Simply put, BRI has enabled an unimaginable acceleration of the commercial sphere, which has become a fundamental driving force for software development in both the civilian and military spheres.

Never lose sight of shi

The existence of the BRI can be explained partially as the result of the retrieval of the shi noticed by Chinese strategists. The essence of shi lies in the ability to adapt constantly to infinite changes in the situation. There are many potential variable factors in human behaviour which has to be constantly considered (Vojta 2014: 72). According to the old Chinese masters, this is the mastery of strategy: ‚those skilled at making the enemy move do so by creating a situation to which he must conform‘ (Pillsbury 2014: 61). China has noted the relative decline of US power and has felt that it is time to become a little more assertive in the final phase of the implementation of the Hundred-Year Marathon. So it came up with the New Silk Road, hoping that this initiative would go unanswered by the American hegemon while accelerating the erosion of U.S. world power by slowly and subtly undermining it (Pillsbury 2014: 61).

China promises a world of prosperity without military conflict, as it has found the BRI to be a tempting proposition for Western observers. We can understand it as waiting to strike until the opportunity arises. At the same time, China is trying to form its own network of allies by economically linking one with the other and, above all, to China itself. The explanation is that China had read the shi and decided to use the nature of the international order for its rise.

Always be vigilant to avoid being encircled or deceived by others.

Through the BRI, China has secured a stronger position in countries considered US allies because they are members of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization. The new Silk Road has allowed China to follow the old rules of warfare, i.e., build its own network of allies while quietly unravelling the opponent’s (Reeves 2014: 142). The BRI is also an entirely new foreign policy that allows it to directly influence distant countries on all the continents. Moreover, with the announcement of the New Silk Road, China has brought to life a cure for its economic problems and has taken advantage of its greatest strengths. Chinese are trying to undermine the US global power within NATO by influencing particular countries, for example, Germany, Greece and Hungary (Xianzum 2021). They are also significantly supporting enemies of the US like Iran or Pakistan, whereas the Taliban was no exception (Ghoshal 2018).

Written by Jiří Egermeier

Bibliography

Beach, Sophie (2017). “Bridging the gap between china a central europe“ Accessed 29 December, 2017, https://chinadigitaltimes.net/2017/12/interview-project-sinopsis-bridging-gap-china-central-europe.

Blumenthal, Dan – Zhang, Linda (2021). “China Is Stealing Our Technology and Intellectual Property“Accessed 2 June, 2021, https://www.nationalreview.com/2021/06/china-is-stealing-our-technology-and-intellectual-property-congress-must-stop-it.

Dahir, Abdi Latif (2018). “China “gifted“ the African Union

a headquarters building and then allegedly bugged it for state secrets“ Accessed 30 January, 2018, https://qz.com/africa/1192493/china-spied-on-african-union-headquarters-for-five-years.

Del Monte, Louis (2019). Geniální zbraně. Umělá inteligence a války budoucnosti. (Taryn Fagernes Agency: San Diego).

Dogan, Asim (2021). Hegemony with chinese characteristics. From the tributary system to the belt and road initiative. (Routledge Taylor a Francis: Oxfordshire).

Garlick, Jeremy (2020). The Impact of China´s Belt and Road Initiative. From Asia to Europe. (Routledge Taylor a Francis: Oxfordshire).

Ghoshal, Debalina (2018). “China´s Path to Global Hegemony: Latest Target Is Syria“ Accessed 20 August, 2018, https://www.gatestoneinstitute.org/12848/china-syria-belt-road.

Godement, Francois – Vasselier, Abigael (2017). China at the Gates: a New Power Audit of EU-China Relations. (European Council on Foreign Relations).

Komarraju, Apoorva (2021). “China will become the AI superpower surpassing U.S. How long?“ Accessed 19 February, 2021, https://www.analyticsinsight.net/china-will-become-the-ai-superpower-surpassing-u-s-how-long.

Liang, Qiao – Xiangsui, Wang (1999). Unrestricted Warfare. (PLA Literature and Arts Publishing House: Peking).

Liu, Xianzum (2021). “Chinese Defense Minister visits Europe to boost military ties, “future join military drills, exchanges likely“ Accessed 25 March, 2021 https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202103/1219500.shtml.

Pillsbury, Michael (2014). Stoletý maraton: Tajná čínská strategie, jak vystřídat Ameriku v roli globální supervelmoci a nastolit čínský světový řád. (Henry Holt and Company: New York).

Prague Post (2019). “Prague´s Charles University Closes Czech-Chinese Center Amid Scandal“ Accessed 15 November, 2019, https://www.praguepost.com/prague-news/charles-university-closes-czech-chinese-center-amid-scandal.

Reeves, Jeffrey (2014). Structural Power, the Copenhagen School and Threats to Chinese Security. The China Quarterly (217), s. 140–161.

Skinner, Chris (2022). “The superpower that is China“ Accessed 13 July, 2022, https://thefinanser.com/2017/08/the-superpower-that-is-china.html.

Vojta, Vít (2014). Umění války. Využití válečných strategií v byznysu. (BizBooks: Brno).

Xiaochun, Ma (1990). The Thirty-six Stratagems Applied to Go. (Yutopian Enterprises).

Zhang, Wenxian – Alon, Ilan – Lattemann, Christoph (2018). China´s Belt and Road Initiative. Changing the Rules of Globalization. (Palgrave Macmillan: London).

643