Indonesia’s Islamic Education System: Incubators for Extremists?

History shows that terrorism is essentially a method of attack and not a philosophy or even a movement. The trend of terrorism in Indonesia since the 1980s has tended to fluctuate, although in general it is characterized by a low stagnant pattern. There is hardly a year without the threats and attacks of terrorism. There are three critical periods related to terrorist attacks in Indonesia, namely the 2001 period, since the terrorist attacks in New York on September 11, 2001, the 2012 period, and the last period in mid-2018 with the suicide bombing in Surabaya. Various groups have been involved in terrorist attacks in Indonesia, starting from Jamaah Islamiyah (JI), Jamaah Ansharut Daulah (JAD), the East Indonesian Mujahidin, to the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS), which tend to be affiliated with JAD. The dynamics of these terror groups have also evolved by starting to target women and children and entering the world of higher education. For instance, five of the seventeen members of the Pepi Fernando network, who at that time were still undergraduate students. A pipe bomb attack was planned by Pepi Fernando and Hendi Suhartono, both graduates of the State Islamic University Syarif Hidayatullah Jakarta (UIN), an Islamic college educational institution with a reputation for supporting Islamic understanding. Pepi had studied at the Tarbiyah Faculty, Islamic Education Department while Hendi Suhartono had studied at the Usuluddin Faculty, Philosophy Department. Another example is the case of alleged radicalism in September 2019 that ensnared a lecturer from Agricultural Institute Bogor (IPB), one of the leading universities in Indonesia.

These cases of violence and terrorism are motivated by the phenomenon of narrow religious fanaticism as a result of the widespread movement of Islamic radicalism. Radicalism has developed so rapidly that it penetrates the boundaries of formal and non-formal education. Based on a National Counter-Terrorism Agency (BNPT) report from February 2, 2016, 19 Islamic boarding schools (pesantren) in Indonesia are indicated to spread radicalism and terrorism. This critical issue that always appears in Indonesia leads to one of the most familiar impacts of religious extremism, namely terrorism. The polemic regarding the issue of terrorism against Islamic education institutions developed wildly and caused public debate, because the mention by BNPT at that time was only a month after the Thamrin Jakarta terror bombing on January 14, 2016. This made the public question Islamic education in general.

To further analyze moderate and extremist ideas in Islamic educational institutions in Indonesia, we need to understand how radicalism in the name of Islam in Indonesia develops. What are the processes and stages of the spread of radicalization in Indonesia? What is the role of educational institutions, especially Islamic education institutions in Indonesia in deradicalization? Given that religious extremism is more communal than individual, should education in Islamic societies be reformed to counter extremist ideas? This raises the most important question – what is expected in the development of Muslims in Indonesia?

Discussion

- Terrorism and Radicalism

It cannot be denied that the discourse of terrorism is closely related to radicalism. Therefore, a correct understanding of radicalism helps us grasp the ideology of terrorism correctly as well. From a linguistic perspective, radicals are much different from terrorists. The term “radicalism” comes from the Latin “radix” which means the “root”, “base”, “bottom”, or it can also mean “the whole”, or “the totality”, making radicals very tough in demanding change. The training in radicalism focuses on ideals and is done in positive ways.

Meanwhile, “terrorism” comes from the word “terror” which means to scare other parties, so terrorism is always carried out in negative ways, by means of spreading fear.

In the case of Indonesia, the very diverse background of culture, the size of the area and the history of the archipelago mean Indonesia has a complex history of radicalism and separatism. To understand the concept of terrorism, we’ll compare it with other adjacent concepts or variants of Islamism (see Table 1).

Tab. 1: Various Variants of Islamism

| Dimension | Literalism | Intolerant | Anti-system | Revolutionary | Violence | Terror |

| Conservatism | √ | √ | √ | |||

| Militant | √ | √ | √ | |||

| Radicalism | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||

| Extremism | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

| Terrorism | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

Source: The Habibie Center, 2019

Given the dynamics and movement patterns of groups in society, radicalism and terrorism tend to converge. Radicalism often becomes an embryo with the potential to grow and produce acts of terrorism. In other words, a radical mindset tends to manifest in acts of terror.

A 2016 UNESCO study shows that there are several factors that encourage and attract radicalism. There are various “driving factors” leading to violent extremism, such as marginalization, inequality, discrimination, persecution, and similar perceptions; limitations on access and quality of relevant education; denial of civil rights and freedoms; and other environmental, historical, and socio-economic complaints. The attraction factors of violent extremist groups include the existence of well-organized extremist groups with effective discourses and programs that provide services, income, and/or jobs in exchange for membership. These groups provide spiritual comfort, a place to belong, and a supportive social network.

Radicalism can be grouped into two levels, namely Discourse – as an abstract idea that supports the use of violent means to achieve goals, and Action – actual acts of violence (see Figure 1).

Fig. 1: Two levels of radicalism

Radicalism has taken the form of actions carried out by hardline group actors by means of violence and anarchism to achieve their main goals in the religious, social, political, and economic fields. In various cases of terrorism that have occurred in Indonesia, for example, radicalism which is believed by elements of the Islamic community is recognized as one of the main factors, of course apart from other factors such as social, political, educational, economic, and others. Radicalism in religion has ultimately spread to various elements of education.

- Radicalism in the Name of Islam in Indonesia

First and foremost, we will examine how Islamic values develop in Indonesia. In terms of political Islam and along with the development of various identity politics, we can trace that there are three directions of Islamic schism in Indonesia:

- Traditionalist

The revival of the Ulama (Nahdlatul Ulama/NU), the largest independent Islamic organization in the world with membership estimates of over 90 million. NU is a traditionalist Sunni Islam movement in Indonesia following the Shafi’i school of jurisprudence. NU was established on January 31, 1926, and is engaged in religious, educational, social, and economic sectors.

- Modernist

After Indonesia’s independence, various other major social-religious organizations emerged as guardians of Masyumi’s modernist Islamic heritage. The modernist Islamic party Masyumi (the Council of Muslim Organizations) was the largest Islamic political party in Indonesia, for example, Muhammadiyah. Muhammadiyah founded by K.H. Ahmad Dahlan in Kauman Village Yogyakarta on November 18, 1912. The main objective of Muhammadiyah is to restore all irregularities that occur in the da’wah[1] process. There are currently 32 registered Islamic mass organizations in Indonesia.

- Radical

Radical responses emerged from the ambitions of political representation and social missions from traditionalist and modernist responses, for example, the revolutionary Islamic militias that were formed within Darul Islam (DI) and Indonesian Islamic Army (TII) – DI/TII. DI/TII was established in 1942, recognized only Shari’a as the valid source of law, coordinated by a charismatic radical Muslim politician, Sekarmadji Maridjan Kartosoewirjo. DI/TII in the context of the Indonesian National Revolution and the struggle against Dutch colonialism. This response is also the seedbed for the contemporary militant branch in Indonesia, especially groups such as Jemaah Islamiyah (JI – Islamic Community).

According to Carnegie (2013b: 60, in Romaniuk 2017: 734), some uneasy tensions in Indonesia arise from the overlapping strands of national, religious, and cultural identity. From statistical data, 87% of Indonesians declared themselves to be Muslim. In fact, there have been many attempts to exploit and limit the ambitions of the Islamic State (Carnegie, 2010: 83, in Romaniuk, 2017: 734). It is not extremism that causes violence because according to Indonesian Muslim people all religious teachings do not support violence. However, Islam is often portrayed in media as a religion fueling violence. Violent extremism attributed to Islam stems from the doctrine of jihad. Jihad, from the point of view of Islam, is not seen as violence – it’s a war. Terrorists argue that Islam does provide a solid basis for fighting (jihad) if it is for religious purposes, including fighting an incompatible regime system with their Islamic political aspirations. According to them, the Indonesian political system is corrupt, therefore it must be replaced by an Islamic system.

Furthermore, according to the views of experts on Islamic radicalism, there are two important characteristics attached to it, which distinguish it from other (non-radical) political Islamic movements: (1) acceptance of the legitimacy of using violence as a means to achieve goals, (2) acceptance of the need for a complete change in the prevailing secular ideology and system into an Islamic ideology and system. According to Abuza (2007), the ideological spectrum of Islamic radicalism ranges between moderate Islamist groups (such as Islamic parties that carry a political Islamist agenda) and extremist-terrorist groups. The radical groups in this category are divided into four:

- Reactive Jihadi groups, namely groups that perpetrated limited violence, such as Laskar Jihad (LJ) during the conflict in Ambon.

- Militant Islamists that carry out violence sporadically and rampage the masses, like the FPI.

- Radical Islamic sympathizers, such as university-based organizations that can accept the platform of radical groups, which fight for the upholding of Islamic law, but do not agree with violence or are not ready to do so, such as Hizbut Tahrir Indonesia (HTI).

- Pure Salafi groups for purification purposes.

Moreover, how does radicalism spread? The processes and stages of radicalization experienced by a person go through stages (see Figure 2):

Fig. 2: The processes and stages of radicalization

Source: National Commission on Terrorist Attacks, 2004.

- Pre-radicalization is the stage where a person lives their daily life before experiencing radicalization.

- Self-identification is the phase when individuals begin to identify themselves with radical ideologies.

- Indoctrination is a phase where a person begins to intensify and focus on what they believe.

- Jihadization is when individuals start acting based on their beliefs. In this stage, individuals can commit various acts of violence motivated by narrow interpretations of religious teachings, vandalism, communal violence, and recidivism. Jihadization can appear in the form of individual initiatives or organizational initiatives.

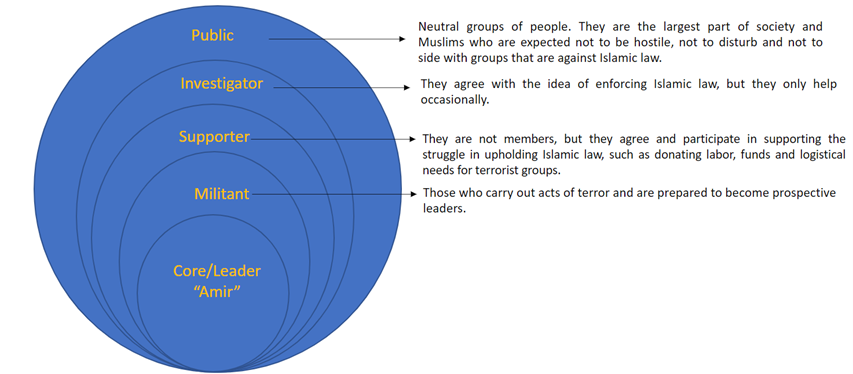

In this stage, radicalization cannot be separated from the recruitment process carried out by radical and terrorist groups in Indonesia. The basis for the recruitment of these radical groups is generally youth who are approached and provided with training both in terms of understanding and physical training. In principle, the recruitment carried out by terrorist groups is to enlarge the concentric circle (see Figure 3).

Fig. 3: The concentric circle of the Recruitment Process in Indonesia

In Indonesia, there are several recruitment strategies and ways of ideological dissemination:

- Direct communication through casual chats and discussions on Islamic teachings, which aims to cultivate existing members and recruit new members.

- Through da’wah[2] in recitations:

- Tablig is da’wah given to the general public.

- Taklim is religious course where the number of participants is limited.

- Tamrin is da’wah in the form of closed recitation.

- Tamhish is a closed recitation, which is a continuation of the previous stage, At this stage, participants will be taught Taklimat Islamiyah Materials (TIM) which is the reference in JI. If a participant understands all TIM and meets the membership criteria, he will be offered to join JI.

- Publish books that highlight the concept of Salafi Jihadism. For example, in the book of Osama Bin Laden – Taujihat Manhajiyah (Signs in the Struggle), JI even published TIM books which were taught in Pesantren it fostered. These books contain the basics of Islam according to the JI version.

- The educational paths, namely through Pesantren Through these, JI can freely teach the various Salafi Jihadism doctrines. However, not all santri[3] who study at the JI’s pesantren will be recruited as members. This recruitment is carried out through a selection process by looking at the backgrounds of the students and their families. The students who do not join JI are expected to become supporters.

- Internet, social media. Radical and terrorist groups also use the internet to disseminate books and information about jihad, promote various activities that have been carried out, convey future activity plans and garner sympathy from the wider community, especially Muslims, and recruit their members.

Furthermore, is religious extremism something dangerous that must be eliminated or at least curbed? Taking extreme positions in religion is not prohibited by the Indonesian political and security authorities. In some cases, even religious extremism that discredits the beliefs of others cannot be classified as illegal because the authorities do not yet have a basis to act against it. It is different if religious extremism turns into religion-based violence. There are many types of religious-based violence – there is violence through the excessive religious crowd, such as those perpetrated by FPI in anti-immorality operations, there is violence that is blasphemy-based, as experienced by Ahmadiyah and Shia people in Lombok and Madura. There were acts of violence that are acts of terrorism, such as those committed by the JI group in Indonesia. Although the three have different patterns, there is one foundational characteristic that unites them all – violence.

- Radicalism in Education

Based on data from the National Counterterrorism Agency (BNPT) in the Coordination Meeting for Combating Radicalism, the religious understanding of the Indonesian people is at the „alert“ level (66.3%). At the second „caution“ level were the students who were the targets of radical ideology. At the third „danger“ level are mosque administrators and madrasah schoolteachers (15.4%). The world of education, both general and religion-based, has the potential to be infiltrated by radicalism and terrorism. Educational institutions can support or promote extremism through a system or curriculum, sometimes even unknowingly.

Educational institutions in Indonesia are very diverse, including Islamic boarding schools (pesantren), madrassas, and schools. Higher education is the highest educational institution which is very vulnerable to be a target of recruitment for radical movements. For example, Gema Liberation, Jamaah Tabligh, FKAWJ (Ahlussunnah Wal Jamaah Communication Forum), or KAMMI (Indonesian Muslim Student Action Unit).

History records the student movement in Indonesia starting in 1908 which marked the emergence of a national movement until it reached its climax in 1998 when students joined laborers. The peasants, the people, the urban poor unite to seize democracy to overthrow the government considered dictatorial, the regime of President Soeharto (New Era). On February 28, 2004, a student movement named Echo of Liberation was officially formed, with the aim of making Islamic ideology the mainstream, even though this is very contradictory to the majority of Muslims in general. The emergence of the Student Liberation Movement in Indonesia is inseparable from the role of Hizbut Tahrir Indonesia (HTI). Echo of Liberation feels called and is obliged to continue the struggle of HTI by carrying out the application of Islamic law in realizing the idea of Islamic caliphate khilafah. This idea is that Islam as the basis of Indonesian politics always creates a clash of interests with ideological nuances. Another incident occurred at the UIN Sunan Ampel (UINSA) campus in Surabaya, where one of the lecturers at UINSA invited students to demonstrate religious issues. This incident is also an example that universities are now being targeted by the proliferation of radical ideologies and ideologies.

Furthermore, Islamic education is one of the institutions that came into the spotlight when inter-religious and ethnic riots broke out in several places in Indonesia. Allegations appeared that Islamic boarding schools have become a „breeding ground“ for radicalism and terrorism in Indonesia. For instances, there are three Islamic boarding schools – Pesantren Al Mukmin Ngruki in Surakarta, Pesantren Al Zaitun in Indramayu, and Pesantren Al Islam in Tenggulung Solokuno Lamongan – all relevant in the discourse of radical Islam in Indonesia.

For example, Almukmin Ngruki became a place for the growth of Indonesian radicalism, in which Muslims and the West were always considered at odds. This pesantren is located in Solo, Central Java, founded by Abdullah Sungkar and Abu Bakar Ba’asyir. Abu Bakar Ba’asyir is well known for his involvement with the JI terrorist group, but he formed the Indonesian Mujahidin Council (Majelis Mujahidin Indonesia or MMI), then Jemmah Anshorut Tauhid (JAT), as a new instrument to promote the application of his version of Islamic Sharia in Indonesia (Wahid, 2014: 78). These salafis only hang out with other people in their group and isolate themselves from the public (Wahid, 2014: 212-14). In terms of formal education, however, this pesantren follows the education prescribed by the Ministry of Religion Indonesia. The formal curriculum and subjects are no different from other Islamic schools under the Ministry. The formal curriculum and subjects are no different from other Islamic schools under the Ministry. Students also take national examinations to pass and receive a diploma that can be used to continue to higher education. However, the Ngruki pesantren also offers informal training sessions for students at the end of their studies which are not included in the curriculum, in which Abu Bakar Ba’asyir’s hardline Salafi doctrine is given by the main reference of the book Aqidah (belief) he wrote. The book teaches absolute obedience to religion. Following any law other than a Salafi understanding of Islamic law is considered polytheistic, blaspheming God Almighty (Fuaduddin et al, 2004: 119). Adhering to and upholding other political systems, such as democracy or polytheism, is one of the main sins in Islam.

Another example is the salafi pesantren in Gresik, Al-Furqon Al-Islami, East Java (Wahid, 2014: 165-208). The teachings conveyed in Gresik are basically maintaining the sanctity of aqidah, the Islamic ritual of closing off associations with people outside the community for fear that it might damage faith.

Currently, Islamic educational institutions are experiencing developments. Initially, the students were not limited to filling in knowledge and building a strong culture in the pesantren, but now they are starting to spread to other worlds of education, such as Islamic schools (mainstream) and integrated Islamic schools (JSIT). JSIT is a school that implements the concept of Islamic education based on the Al-Quran and As-Sunnah. The operational concept of JSIT is an accumulation of the process of civilization, inheritance, and development of Islamic teachings, Islamic culture, and civilization from generation to generation. JSIT combines general education and religious education into one curriculum fabric. From the categories mentioned above can identify the differences and similarities:

- The similarity in the aspects: power lines; giving punishment; giving direct instructions; expectations regarding memorization skills; infrastructure; and the policy environment.

- Meanwhile, the difference: openness; integration between school, community, and society; identity, interpretation; and a view of diversity.

- Principals of mainstream Islamic schools support more open and integrated schools. They recruit teachers from various backgrounds and understand that a person can have many identities other than their identity as a Muslim. On the other hand, the principals of the Islamic school network lead the school behind closed doors and separate from the community and society. They lead schools that teach that the idea of a pure ‚Muslim‘ identity (as defined by the school) is essential to their lives as Muslims. In addition, they teach students to view diversity as ‚the other side‘, different, not part of their group, and incompatible with the path of religion.

From the examples above, there are two factors that are fundamental to the occurrence of radicalism in educational institutions. First, there have been changes in religious-based educational institutions. Second, an internal metamorphosis of forms and strategies has been happening in the radical movements.

It must be underlined that the education of religious values in schools does not necessarily mean that students have the ability to recognize radical or extremist propaganda. The cooperation of all parties involved in the learning process (internal and external) also has a share in student learning outcomes.

Conclusion

Indonesia is the country with the largest Muslim population in a country (more than 230 million people are Muslim), but not governed by Islamic law. It is clear, however, that the influence of Islamic principles and ethics on Indonesian society, politics, and economy is enormous. The Muslim community is not homogeneous: there are moderate and conservative camps, along with the development of various identity politics: Traditionalist: Nahdlatul Ulama (NU – Revival of the Ulama), Modernist: Masyumi, Muhammadiyah, Radical: DI and TII.

The wave of Islamization in Indonesia made many Indonesian Muslims (consciously or unconsciously) strengthens their Islamic identity. This background will bring up certain groups, usually small and without political power, to impose their version of conservative Islam on society and politics. Terrorist groups use Islam as a platform to gain support from those marginalized and mistreat Muslims, but do not serve in the interests of Islam.

How Indonesian government reacts? The President of the Republic of Indonesia Joko Widodo emphasized the importance of various approaches in dealing with terrorism – not only the security and legality – but more importantly sociocultural, educational and religious approaches. Additionally, Detachment 88 as the front line in dealing with terrorism in Indonesia has so far used several soft approaches, namely ideological and religious approaches; sociocultural and political approaches; security and rights, or juridical approach in collaboration with BNPT.

Furthermore, radicalism is caused mostly by a narrow interpretation of a phenomenon. Radicalism is an ideology-based understanding. The ideology comes together with belief. It’s not easy to overcome these problems, there must be a structured and systematic concept in order to enter into institutional instruments. One of them is through education. Education is said to be an indicator of the progress of a nation’s civilization. What is expected through education? It is hoped that it can fight extremist thoughts and behavior by teaching the values of citizenship, democracy, and tolerance, which are in line with the goals of Indonesia’s national education as stated in Act of the Republic of Indonesia on the National Education System (Law No. 20/2003 article 3).

In fact, it’s quite disappointing that the administration of education in Islamic education institutions has been inadequate in the past. This is evident, for example, in the licensing and accreditation processes of Islamic schools, which are occurring irregularly at best. To stem radicalism focus on significant transformations are also seen in reforming the education system through the curriculum, learning processes, learning activities and media used varied learning experiences, and appropriate learning planning. Counter-ideology requires hard work in education at all levels through the following methods: (a) Radicalism can be eliminated through fostering certain perspectives on phenomena including moderate, fair, balanced, and universal thinking; by strengthening the pattern of internal school cooperation networks and external networks between schools and communities; (b) Islamic education institutions can adopt a more modern management system and try to catch up with the development of science and technology and adopt comprehensive learning by making efforts to evenly integrate general science and Islamic knowledge. Examples of development and application of a curriculum for learning Islamic studies with the substance of moderate Islam using contextual studies to dissect the thoughts of Islamic leaders are emerging. For example, the State Islamic University (UIN) Sunan Ampel Surabaya, East Java will include a course with the theme of the Nusantara Islamic Movement.

In particular, addressing the problem of extremism in Indonesian Islamic schools can be done through developing cross/inter-faith activities, encouraging the adoption of Indonesian Muslim identity, and supporting the idea of individuals who have mixed identities. Furthermore, integrating critical thinking skills into the curriculum rather than emphasizing memorization methods would create proactive redundancies throughout the system to address issues of openness, integration, identity, and diversity. Moreover, through a Brain-Based Learning approach that combines several aspects such as emotional, social, cognitive, physical, and reflective. This approach seeks to optimize the workings of the brain in capturing information that comes from outside the self through the promotion and education of positive attitudes and high motivation. The principle lies in the increase in emotional intelligence (EQ). The world would experience a crisis if the overall intellectual intelligence (IQ) trumps emotional intelligence (EQ), leading to people that are smart, but sadistic.

At that point, what is expected in the development of Muslims in Indonesia? It is hoped that they will be able to raise Muslims who understand modern religious teachings, understand Indonesian characteristics along with a global perspective.

Written by Laurencia Krismadewi

[1] Means issuing a summons or making an invitation. It refers to the proselytizing or preaching of Islam and the exhortation to submit to Allah.

[2] the act of inviting or calling people to embrace Islam.

[3] Students of pesantren, a kind of Islamic boarding school in Indonesia

References

[1] Abuza, Zachary. 2007. Political Islam and Violence in Indonesia. New York: Routledge, 2007. p.79

[2] Ali, H. 2017. Menakar Jumlah Jamaah NU dan Muhammadiyah. Available online at https://hasanuddinali.com/2017/01/19/menakar-jumlah-jamaah-nu-dan-muhammadiyah/

[3] Directorate General of Higher Education, Ministry of Education and Culture of the Republic of Indonesia. Available online at: diktis.kemenag.go.id/NEW/index.php?berita=detil&jenis=news&jd=162

[4] East Java Regional Police Chief Peel Radicalism Understanding at UINSA Campus. 2016. Available online at https://surabaya.tribunnews.com/2016/09/07/kapolda-jatim-kupas-paham-radikalisme-di-kampus-uinsa-ternyata-ini-tunjuk

[5] Indonesian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. 2016. Indonesia and countermeasures against terrorism. Available online at: https://www.kemlu.go.id/id/keb Policy/isu-k Khusus/Pages/Penanggulangan-Terorisme.aspx

[6] Gallagher, Mary; Lindsey, Tim; dan Parsons, Jemma. 2010. Curriculum Review. Report from the Faculty of Tarbiyah and Teacher Training, UIN Jakarta. Melbourne: AsiaLaw Group Pty Ltd.

[7] Indonesian Student Movement. Available online at https://id.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pergerakan_mahasiswa

[8] Law on the National Education System of the Republic of Indonesia (No. 20/2003). Available online at http://planipolis.iiep.unesco.org/sites/planipolis/files/ressources/indonesia_education_act.pdf

[9]List of Islamic mass organizations in Indonesia. Available online at https://id.wikipedia.org/wiki/Daftar_organisasi_massa_Islam_di_Indonesia

[10]Muhammadiyah. Available online at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Muhammadiyah; https://muhammadiyah.or.id/

[11]Muzoffari, Mehdi. 2007. What Islamism? History and definition of a concept. Totalitarian Movements and Political Religions.Vol. 8, No. 1, March 2007, p.21-42.

[12] Nahdlatul Ulama. Available online at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nahdlatul_Ulama; https://www.nu.or.id/

[13] National Counter Terrorism Agency (BNPT). Available online at https://www.bnpt.go.id/

[14] National Commission on Terorist Attacks. 2004. The 9/11 Commission Report: Final Report of the National Commission on Terorist Attacks Upon the United States. New York: W.W. Norton, 2004, p.150–152.

[15]Osman, Sulastri and Navhat Nuraniyah. 2014. Indonesia’s Cyber Counterterrorism: Innovation Opportunities for CT Policing. Available online at https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/175336/RSIS0032014.pdf

[16] S.N. Romaniuk et al. 2017. The Palgrave Handbook of Global Counterterrorism Policy. DOI: https://10.1057/978-1-137-55769-8_34.

[17]Syam, Nur. 2009. Challenges of Indonesian Multiculturalism. Yogyakarta: Kanisius.

[18]The Habibie Center. Available online at : www.habibiecenter.or.id

[19]Ulama, Islamic Organizations, and Islamic Militias. 2019. Indonesia’s Islamic Revolution. p.66 –78. DOI: https://doi:10.1017/9781108768214.005.

[20]Understanding Integrated Islamic Schools. Available online at https://jsit-indonesia.com/sample-page/peng Arti-school-islam-terpadu/

[21] Wahid, Din. 2014. Nurturing the Salafi Manhaj: A Study of Salafi Pesantrens in Indonesia Kontemporer. Disertasi PhD. Utrecht: Universiteit Utrecht

[22] Wazis, Kun. 2017. Radicalism Issues – Terrorism and Islamic Boarding School education (Pondok Pesantren). Republika. Available online at https://republika.co.id/berita/orn905396/isu-radikalismeterorisme-dan-pendidikan-ponpes

1094