Mozambique and the Fight Against Extremism

Since October 2017, the violence perpetrated by non-state armed groups in the northern province of Cabo Delgado in Mozambique has resulted in more than 530,000 internally displaced people (IDPs) and over 2000 people killed (UNHCR 2021). One of the main insurgent group, Ansar al-Sunna -called by the locals “Al-Shabaab” (the youth) due to the similarities with the Somali terrorist group of the same name- has carried out more than 700 attacks and has strengthened its ties with other international terrorist groups, forcing the Mozambican authorities to implement counterterrorism measures in the region. Nonetheless, the military operations have not brought the results hoped, on the contrary, the security forces have been responsible for human rights violations and the intervention of external actors, namely Private Military and Security Companies (PMSCs) and countries with economic and political interests- Russia, France and Portugal- have contributed to worsening the security situation in the region, which could have repercussions in the neighbouring countries.

This paper will therefore give an overview of the primary causes and consequences of the rise of jihadism in northern Mozambique as well as the military responses that have been taken by regional and international actors to try to deescalate violence. In the final part of the article, I will argue that a militarized approach of counterterrorism perhaps is not the solution for Mozambique and that instead different measures that address the underlying causes of violence and extremism should be taken into consideration.

The emergence of Islamic extremism: Ansar al-Sunna

In 2017 Islamist militants, going with the name of Ansar al-Sunna, started to target civilians with the purpose of establishing an Islamic state in the northern province of Cabo Delgado. It is believed that, before becoming an insurgency group, Ansar al-Sunna started in 2015 as a religious movement formed by followers of Kenyan radical Cleric, Aboud Rogo Mohammed, that moved to Mozambique after his death (Bukarti and Munasinghe 2020: 4). It is important therefore, to analyse which factors have contributed to the radicalization of this group and ultimately have determined its growth beyond Mozambican borders.

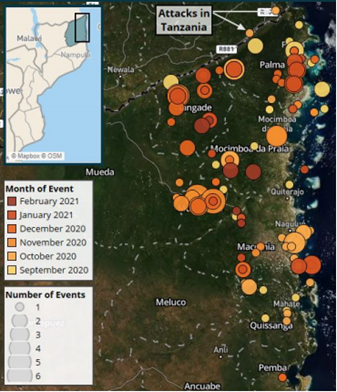

The jihadi insurgency in Capo Delgado has benefitted from unique political and socio-economic circumstances. First of all, we should mention that despite the country is largely Catholic, in the northern province the majority of the population is Muslim (58%). Moreover, Capo Delgado has been historically neglected by the Mozambican central government, which combined with the high levels of illiteracy, have made the province the perfect breeding ground for radicalization. In addition to that, ethnic cleavages resulting from decolonization and the conflict fought after the independence from Portugal, as well as the corruption and the ineffective response of the government security forces, have accelerated the growth and scope of Ansar al-Sunna. Going from a religious movement, transforming into small cells attacking mostly civilians with rudimental arms such as machetes and knives, Ansar al-Sunna became more sophisticated and better equipped and started targeting government officials. Rapidly, the insurgent group has spread in the northern province and it has developed ties with other terrorist groups. Allegedly in mid-2019, the Islamic State (IS) became to claim attacks in the same area where Ansar al-Sunna was operating and, in June of the same year, the insurgency in Mozambique became officially part of the Islamic State’s Central Africa province (ISCAP) (Lister 2020: 35). Beyond the IS, possible links of Ansar al-Sunna have been found with other terrorist groups, such as the Somali Al-Shabaab and Boko Haram (Makonye 2020: 59). As reported by the Tony Blair Institute for Global Change (2020), Ansar al-Sunna is following an upward trajectory in violence (see the graph below) and in 2020 has been launching more than 20 attacks per month (see the image below).

Source: Tony Blair Institute for Global Change, June 2020, https://institute.global/policy/mozambique-conflict-and-deteriorating-security-situation

Source: ACLED, 17 February 2021, https://acleddata.com/2021/02/17/cabo-ligado-weekly-8-14-february-2021/

The Ansar al-Sunna’s leadership is inspired by international jihadism and it holds the same goals of establishing an Islamic State by following Sharia while rejecting the government’s secular education system (Pirio, Pittelli and Adam 2018). For the last years, the group has in fact prevented children to attend schools and it has instead taught them their version of Islam in two mosques in Mocímboa da Praia, until they reached the age to join the militias (ibid). It is clear therefore, that among the driving factors of the emergence of jihadism in northern Mozambique there is a strong grievance of the youth resulting from misgovernment and unequal distribution of resources that has ultimately led to an economic and political discontent; there is the influence of other terrorist groups- from Somalia, Kenya and Tanzania- that have contributed to train the Ansar al-Sunna’s militias and to spread their fundamentalist interpretation of Islam; and ultimately there is the military response of the Mozambican security forcers and other external actors that have contributed to the exacerbation of violence and the radicalization of the insurgency.

The Government Response

Since the beginning of the insurgency in Capo Delgado, the Mozambican government has opted for a militarized response instead of addressing the root causes of the unrest: poverty, marginalization and ethnic cleavages. The recent discoveries in the province of natural gas and oil, which are worth more than 60$bn in finance deals, have undoubtedly influenced the choice of the government of using an “iron fist” to stop the insurgents. In this regard, the government started to close mosques suspected to be affiliated with Ansar al-Sunna. Nonetheless, in a province where the majority of the population is Muslim, these measures have only increased the mistrust of the Muslim community towards the government, while on the other hand reinforcing the support for Ansar al-Sunna. In addition, security forces in Capo Delgado have been responsible for serious human rights abuses in their counterterrorism operations, by arbitrarily detaining, ill-treating, and summarily executing dozens of people they suspected of belonging to the Islamist group (Human Rights Watch 2018).

Additional measures taken by the government of Mozambique included the approval in 2018 of new counterterrorism legislation: the “Legal Regime for Repression and Combating Terrorism”, which strengthened punishment for anyone affiliated to terrorist groups -providing of receiving training for terrorist purposes- or taking part to terrorist acts (Bukarti and Munasinghe 2020: 8). As a result of the ties of Ansar al-Sunna with other terrorist groups and following the cross-border attacks in neighbouring Tanzania, the government has moved also to increase border security.

Private Military and Security Companies (PMSCs)

The unsuccess of Mozambican military operations has brought the President, Filipe Nyusi, to seek the help of several Private Military and Security Companies (PMSCs). The first PMSC to enter the country in 2018 was the Russian “Warner Group”, defined by the United States Institute of Peace (2020) as a “shadowy mercenary outfit with direct ties to the Russian President, Vladimir Putin”. Nonetheless, after the loss of 7 of their members, the Russian contractor decided to pull out from the country just a few months after arriving.

To replace the Warner Group, the government hired the Dyck Advisory Group (DAG) with the principal aim to conduct airstrikes against Ansar al-Sunna positions in Cabo Delgado (Bukarti and Munasinghe 2020: 3). Despite some setbacks, the aerial support provided by DAG has successfully prevented the insurgency to gain strategic positions along the coast. In July 2020, the government of Mozambique has extended the contract with DAG for further 8 months, in which the PMSC will offer not only operational support on the ground but also training support to the Mozambican forces (Simonson 2021). Moreover, another contract has been stipulated with Paramount Group, a global aerospace and technology company that will provide equipment- armoured vehicles, aircraft and naval vessels- and training.

International and Regional Response

The economic interests in the region and the threat that Ansar al-Sunna poses for the spreading of jihadism in East Africa, have prompted other countries to offer their support to the government of Mozambique. In 2018, Egypt, India and Russia signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) to offer training and resources in the fight against Islamist extremism. Another MoU was signed with the UK to enhance defence cooperation (ibid). Concerns on the security situation in Cabo Delgado have been expressed also by the African Union and the European Union; in particular France- given that Total is one of the main gas companies operating in the region- and the formal colonial ruler of Mozambique, Portugal, have offered logistical and training support to the counterterrorism efforts.

While seeking international intervention, the Mozambican government has been so far reluctant to reach for regional support. As explained earlier in the article, it has instead opted for the opposite strategy of tightening its border security. The lack of regional coordination will only benefit Ansar al-Sunna and the spread of violent extremism in the region.

Alternative approaches to the military response

The counterterrorism response in Cabo Delgado has been unorganized and the government of Mozambique has proved to lack a long-term strategy to solve the security issue in the region. The decision to fight violent extremism with PMSCs has only backfired, and while minimal success has been recorded in stopping the insurgency to spread in some key cities, the military operations did not tackle the root causes that determined the emergence of Ansar al-Sunna. On the contrary, the deployment of army units has only pushed the Islamist insurgency to transform its organization and combat tactics, finally resulting in more violent attacks, which have also crossed the Mozambican borders. The lack of transparency characterizing PMSCs has also determined a certain difficulty in sharing information effectively with national and regional forces. Moreover, the Mozambican security forces have proved to be poorly equipped and untrained to fight violent extremists. Attacks by Ansar al-Sunna in Cabo Delgado in the first nine months of 2020 have doubled in respect of those in 2019 (ACLED 2021). Despite some analysts have described the Ansar al-Sunna as a new group composed of marginalized young people, it cannot be ignored the potential threat that this group poses for the spreading of Islamist violent extremism in south-eastern Africa, especially considering its rapid evolution and its strong ties with external terrorist networks.

As proved by the protracted counterterrorism operations in the Sahel, the Horn of Africa and Lake Chad Basin, a purely militarized approach is short-lived if not combined with a more holistic strategy that addresses the economic, political, religious and ethnic underlying causes of violence. In the case of Mozambique, therefore, the government should implement development and educational programs in Cabo Delgado to solve the socio-economic drivers of Islamist extremism, while at the same time dismantle the ideological narratives of Ansar al-Sunna that keep attracting young people into the jihadist movement. Additionally, a more detailed economic plan for Cabo Delgado should be presented, in cooperation with the energy companies investing in the province. There is an urgent need also to face the humanitarian crisis and to take into consideration the needs of the 530,000 IDPs, in order to ensure a safe return to their homes.

At the international level, the external ties that are providing training and financial support to Ansar al-Sunna should be dismantled through the use of sanctions. Furthermore, the insurgency group should be designated as a terrorist group and his financial activities should be closely monitored.

To conclude, as highlighted by the United States Institute of Peace (2020), the escalation of violence in Cabo Delgado is concerning, nonetheless, it has not yet reached the severity of conflicts in the Sahel and the Horn of Africa. The overly-militarized counterinsurgency measures alone cannot solve the security issues in northern Mozambique, but instead, reconciliation and peacebuilding efforts should be implemented at the grassroots level, to solve ethnic division and economic marginalization.

Written by Giulia Messeri

Bibliography:

ACLED (2021). Cabo Ligado Weekly: 8-14 February 2021. 17.02.2020 (https://acleddata.com/2021/02/17/cabo-ligado-weekly-8-14-february-2021/, 18.02.2021)

Al Jazeera (2020). Desperate’ situation in northern Mozambique: UN rights chief (https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/11/13/un-rights-chief-says-desperate-situation-in-mozambique 14.02.2021)

Bukarti, A.B. and Munasinghe, S. (2020) The Mozambique Conflict and Deteriorating Security Situation. Tony Blair Institute for Global Change. (https://institute.global/policy/mozambique-conflict-and-deteriorating-security-situation, 14.02.2021)

Human Rights Watch (2018) Mozambique: Security Forces Abusing Suspected Insurgents. 04.12.2018 (https://www.hrw.org/news/2018/12/04/mozambique-security-forces-abusing-suspected-insurgents, 14.02.2021)

Lister, T. (2020) Jihadi Insurgency in Mozambique Grows in Sophistication and Reach. Volume 13, Issue 10. (https://ctc.usma.edu/jihadi-insurgency-in-mozambique-grows-in-sophistication-and-reach/, 14.02.2021)

Makonye, F. (2020) The Cabo Delgado Insurgency in Mozambique: Origin, Ideology, Recruitment Strategies and, Social, Political and Economic Implications for Natural Gas and Oil Exploration. (https://journals.co.za/doi/10.31920/2732-5008/2020/v1n3a4, 14.02.2021)

Pirio, G., Pittelli, R. and Adam Y. (2018) The Emergence of Violent Extremism in Northern Mozambique. 25.03.2018 (https://africacenter.org/spotlight/the-emergence-of-violent-extremism-in-northern-mozambique/, 15.02.2021)

Simonson, B. (2021). Mozambique and the Fight Against Insurgency. 08.02.2021 (https://globalriskinsights.com/2021/02/too-many-mercenaries-in-mozambique/, 15.02.2021)

UNHCR (2021) Cabo Delgado Situation. 12.02.2021 (https://data2.unhcr.org/en/documents/details/84879, 14.02.2021)

United States Institute of Peace (2020) Mozambique’s Crisis Requires a New Playbook to Fight Extremism. 03.12.2020 (https://www.usip.org/publications/2020/12/mozambiques-crisis-requires-new-playbook-fight-extremism, 14.02.2021)

United States Institute of Peace (2020) 2020 Trends in Terrorism: From ISIS Fragmentation to Lone-Actor Attacks. 08.01.2021. (https://www.usip.org/publications/2021/01/2020-trends-terrorism-isis-fragmentation-lone-actor-attacks 14.02.2021)

Photo:

Filitz, J. (2018, July 31). „Recent conflict in Mozambique underscores the root causes of fragility“. Retrieved from: https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2018-07-31-recent-conflict-in-mozambique-underscores-the-root-causes-of-fragility/

1107